GANDHINAGAR: In the high-pressure environment of Indian schools, a child’s success is usually measured by report cards.

But a growing body of evidence suggests that the most critical data points—a child’s ability to manage a temper tantrum, share a toy, or navigate a playground disagreement—are often the hardest to measure.

A new study published in Acta Psychologica reveals that the two most influential groups in a child’s life, parents and teachers, are often looking at the same child but seeing two completely different versions of their social and emotional health.

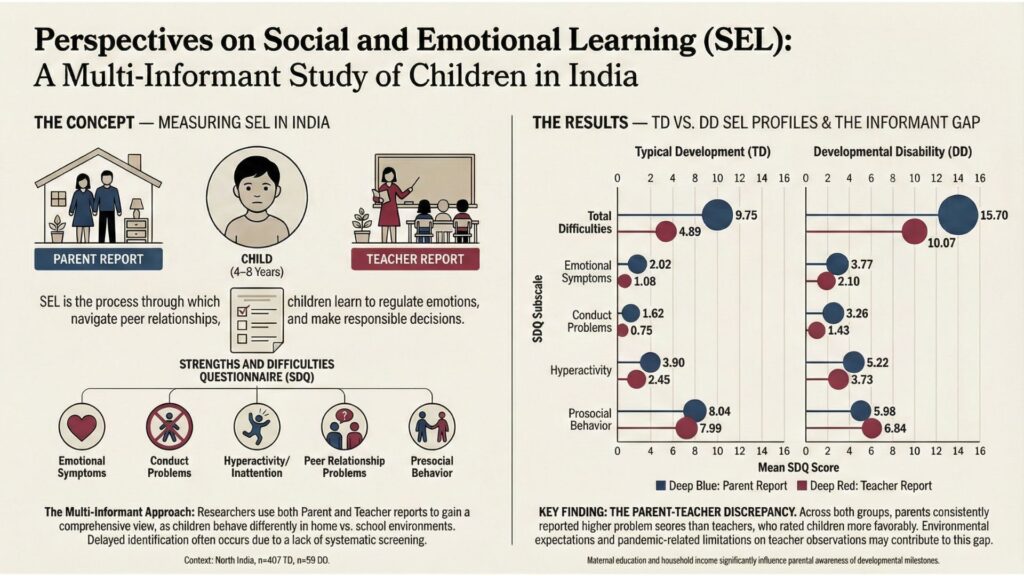

The parent teacher gap by Shyno baby paulThe research was spearheaded by Hina Sheel of De Montfort University Dubai, alongside Lidia Suárez and Nigel V. Marsh from James Cook University in Singapore. By analyzing 466 children aged 4 to 8 across Chandigarh, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, and the National Capital Region (NCR), the team sought to understand how India assesses Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)—the vital skills that allow children to regulate emotions and build relationships.

The Missing Metric of Success

Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) is the “invisible curriculum” of early childhood. Through SEL, children learn to apply the attitudes and skills necessary to make responsible decisions and handle peer conflict. Experts warn that when these skills are neglected, the consequences are severe, ranging from academic failure to long-term psychiatric disorders.

In India, however, screening for these issues is often delayed until a child’s behavior becomes so disruptive that it requires intensive intervention. To bridge this gap, the researchers utilized the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), a 25-item screening tool that tracks five key areas: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behavior.

The Great Disconnect: Parents vs. Teachers

The core of the study involved a direct comparison between how 407 parents of typically developing (TD) children and 59 parents of children with developmental disabilities (DD) viewed their children’s skills, compared to the reports of their teachers.

The findings were stark: parents and teachers rarely agreed on the severity of a child’s struggles. Across almost every metric, parents reported significantly higher levels of concern than teachers. For typically developing children, parents expressed more worry regarding emotional symptoms, conduct problems, and hyperactivity.

When it came to children with developmental disabilities, the gap widened further. Parents of children with DD reported severe problems across all scales, whereas teachers—while recognizing the difficulties—tended to provide more optimistic ratings. For instance, on the “Total Difficulties” score, parents of children with disabilities reported a 47% “abnormal” rate, while teachers recognized a higher 54% in that category but generally reported more prosocial behavior than parents did.

Why the Views Diverge

Researchers suggest this discrepancy isn’t necessarily because one group is “wrong,” but because they see children in different ecological contexts.

- The Comparative Lens: Teachers observe a child in a room of thirty or forty peers. They use a “comparative lens,” viewing a child’s high energy as “average” relative to a classroom of fifty other children.

- The Home Sanctuary: At home, children feel a “safety” that allows them to express negative behaviors they might suppress at school.

- Environmental Expectations: The structured demands of a primary school classroom may force a child to behave differently than they do in the unstructured environment of a living room.

Culture: The Silent Script of Indian Parenting

The study emphasizes that a child’s development in India is not a solo journey but a collective endeavor shaped by “cultural scripts”.

In North India, the educational level of the mother emerged as a pivotal factor. Highly educated mothers were found to be more informed about developmental milestones and more receptive to identifying social-emotional struggles. On the other hand, teachers in regions like Punjab often attributed behavioral issues to a lack of parental involvement or the stresses of low socioeconomic status.

Geography and gender also play a role. The research noted that in Northern India, gender inequality remains pronounced, with boys often prioritized for schooling over girls. This social reality can affect which children are even present in the classroom to be assessed for SEL in the first place. Likewise, the study had to create a new Hindi translation of the SDQ because the existing versions available online contained translation errors, highlighting the need for culturally and linguistically precise tools in a country as diverse as India.

The COVID-19 “Blind Spot”

The timing of the research—conducted between August and December 2021—added a layer of complexity: the COVID-19 pandemic. With schools shifting to digital platforms, the traditional ways teachers monitor social health were effectively “blinded”.

In a physical classroom, a teacher can notice if a student is being excluded on the playground or read subtle nonverbal cues in body language. On a Zoom screen, those cues vanish. Teachers reported that the pandemic led to reduced communication and increased social anxiety among students.

Meanwhile, parents were “sampling” their children’s behavior more than ever before because of lockdowns. This constant proximity likely heightened parental anxiety, leading them to report more social deprivation and pressure than they might have in a pre-pandemic world.

A Call for a “Multi-Informant” Future

The researchers argue that the “perception gap” is actually a reason to include both voices in clinical assessments. Relying on a single source—like just a teacher’s report—risks “under-identifying” children who are struggling quietly. Conversely, relying only on parents can lead to a higher number of “false positives” due to individual parental anxiety.

The study concludes that the SDQ is a highly effective, low-cost tool for India’s inclusive education goals, such as the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan program, which aims to support all learners regardless of ability. By acknowledging that a mother’s concern and a teacher’s observation are two sides of the same coin, India can move toward a system where social skills are valued as much as math scores.

As the authors Sheel, Suárez, and Marsh note, the goal is to identify at-risk children early—ensuring that every child, whether typically developing or with a disability, has the emotional support they need to succeed in the long run.