GANDHINAGAR: Social connections are a cornerstone of human well-being, influencing everything from our physical health to our emotional resilience. At the heart of these intricate relationships lies a powerful brain chemical often dubbed the “cuddle hormone”: oxytocin.

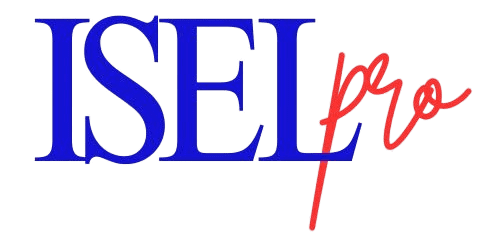

While commonly associated with romantic love and parental bonding, recent scientific discoveries are unveiling a more nuanced and multifaceted role for oxytocin, particularly in the formation of friendships and its profound impact on social and emotional learning across all age groups.

This article delves into the fascinating world of oxytocin, exploring how it facilitates our earliest attachments, shapes our friendships, and even helps us cope with social loss. We will draw upon cutting-edge research, primarily from studies on prairie voles—a species remarkably similar to humans in their social behaviors—to unravel the surprising chemistry behind our deepest connections.

Oxytocin: More Than Just the “Love Hormone”?

Oxytocin is a neuropeptide, a chemical messenger released in the brain during various social interactions, as well as during significant life events such as sex, childbirth, and breastfeeding. Historically, it has been widely recognized for its contribution to feelings of attachment, closeness, and trust, earning it the popular moniker “love hormone”.

The assumption has been that oxytocin is fundamentally important for mammalian pair bonding and good parenting.

However, groundbreaking recent research, particularly involving prairie voles, has begun to challenge this long-held dogma. Scientists, including Nirao Shah from Stanford Medicine and Annaliese Beery from UC Berkeley, have conducted studies that reveal that oxytocin may not be as essential for long-term romantic attachment and good parenting as previously thought.

A key difference in this newer research lies in the methodology. Earlier studies often relied on drugs that blocked or mimicked oxytocin’s binding. However, these pharmacological agents can be imprecise, diffusing to unintended areas or persisting longer than intended, potentially leading to misleading results.

To overcome these limitations, researchers utilized a more meticulous genetic technology: CRISPR, to specifically delete the gene for the oxytocin receptor (OTR) in prairie voles. This allowed for a precise examination of how the complete absence of oxytocin signaling through its primary receptor impacts social behaviors.

The results were surprising. Prairie voles lacking oxytocin receptors still exhibited monogamous behaviors and conscientious co-parenting. They continued to spend time with their mates long after mating and displayed protective behaviors towards their pups, with mothers nursing and fathers helping to keep the young warm, clean, and close.

While these voles did take longer to form mate bonds, the ultimate formation of these bonds did not require oxytocin signaling through its receptor. This indicates that, while oxytocin might facilitate the speed of bond formation, it is not indispensable for the existence of long-term romantic and parental relationships in prairie voles.

These findings have significant implications, as they may explain why numerous clinical trials administering oxytocin as a drug for conditions characterized by social impairments, such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder, have yielded mixed or disappointing results.

As Nirao Shah put it, “It looks as though people may have been barking up the wrong tree” when assuming oxytocin was the sole driver for certain social behaviors.

The “Friendship Hormone”: Oxytocin’s Role in Peer Relationships

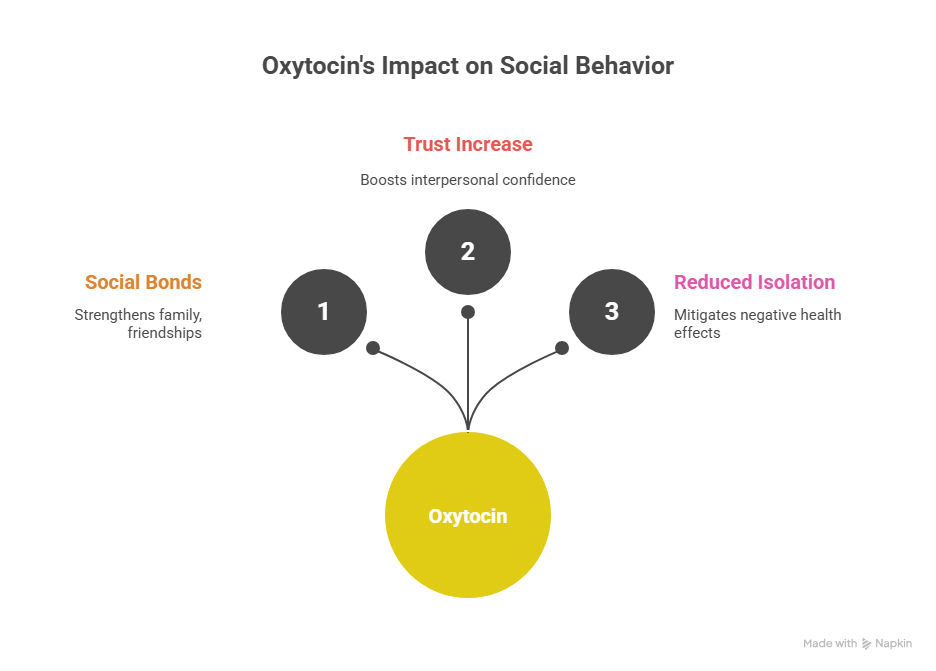

If oxytocin isn’t strictly essential for romantic love and parenting, what is its primary role in social bonding? Recent UC Berkeley research suggests that oxytocin is critically important for the rapid formation of deep friendships.

To understand this, it’s helpful to define friendship. In a scientific context, friendship refers to pairs of individuals who engage in frequent and consistent affiliative interactions that are non-aggressive and non-reproductive, differentiating them from non-friends.

This includes behaviors like spending time together, grooming, huddling, and even forming alliances. Prairie voles are an ideal model for studying these peer relationships because, much like humans, they naturally form stable and selective bonds.

Studies on OTR-deficient prairie voles revealed key insights into oxytocin’s role in friendship:

Delayed Friendship Formation:

Normal voles typically form a preference for a peer partner after about 24 hours of close proximity. However, voles lacking oxytocin receptors showed no such preference within that time frame, taking up to a week to establish a peer preference. This suggests oxytocin is not required for a friendship to eventually form, but it is crucial for facilitating it quickly and efficiently in the early stages.

Lack of Selectivity:

Oxytocin appears to be vital for social selectivity – that is, determining who an animal is social with, rather than merely how social they are in general. In a “cocktail party” experiment where voles could interact in a mixed group, normal voles tended to stick with their known friends before mingling, whereas OTR-deficient voles immediately mixed with strangers, acting as if they didn’t have a specific partner.

Reduced Social Reward:

When given the option to work (e.g., press a lever) to access a friend or a stranger, OTR-deficient voles did not show a preference for their friends, unlike wild-type voles. This indicates they lacked the intrinsic social rewards normally associated with selective attachments.

Altered Aggression towards Strangers:

Voles lacking oxytocin receptors were also notably less aggressive towards strangers and less avoidant of them. This highlights a fascinating dual role for oxytocin: it contributes to the prosocial desire to be with known friends and the “antisocial” side of rejecting unfamiliar individuals, a parallel to human in-group/out-group dynamics.

Further investigation using newly developed oxytocin nanosensors confirmed that voles lacking OTRs had lower oxytocin release and fewer release sites in the nucleus accumbens, a key brain region for social reward. This demonstrates that the absence of the receptor impacts the very regulation of oxytocin itself, affecting social behavior.

Oxytocin and Family Bonds: From Parent-Child Connections to Long-Term Well-being

While the latest research shifts the emphasis of oxytocin’s role in mate bonding, its importance in the broader context of family relationships, particularly parent-child bonds, remains profound. These early attachments are fundamental for a child’s psychological development, physical health, and overall well-being throughout life. Disruptions in these relationships can have long-lasting negative consequences, including increased risk for depression, anxiety, and other health issues.

Oxytocin, along with arginine vasopressin (AVP) and dopamine, is deeply involved in mediating maternal and paternal care. For instance, central oxytocin administration has been shown to induce maternal behavior in rats and increase responsiveness in ewes, even without natural parturition.

In human mothers, increased plasma oxytocin levels during pregnancy correlate with maternal bonding to the fetus, and high levels in the first trimester predict the amount of postpartum maternal behavior, including affectionate gaze, vocalizations, and positive affect.

Oxytocin also plays a role in paternal behavior, with transient increases observed in male prairie voles exposed to pups and its administration reducing food transfer refusal to infants in marmosets.

Early life experiences are critical in shaping an individual’s capacity for social bonding later in life. Studies in prairie voles illustrate this vividly: pups raised by single mothers received less parental nurturing, and as adults, the females showed impaired partner preference formation.

Importantly, research indicates that natural variations in oxytocin receptor density in the nucleus accumbens can predict an individual’s resilience to the effects of early-life social neglect. Females with naturally high OTR densities were able to form adult social attachments normally, even after experiencing early social isolation, suggesting a protective effect.

This indicates that parental licking and grooming may stimulate oxytocin release, and a higher OTR density allows for more effective oxytocin signaling, which strengthens the neural circuits essential for future social attachments.

These findings are crucial, as they echo observations in humans where childhood abuse and neglect are associated with lower oxytocin concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid. The development of socio-cognitive skills, including aspects of “Theory of Mind” (understanding others’ mental states), begins early in life and is significantly influenced by social interactions and environment.

The Broader Impact: Trust, Social Loss, and Therapeutic Potential

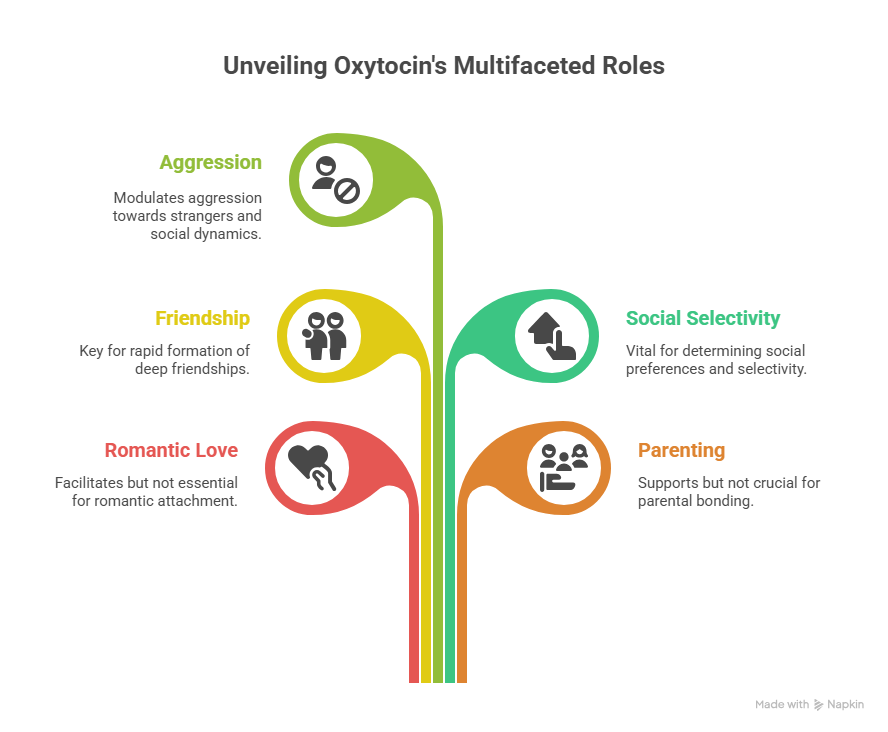

Beyond friendships and family, oxytocin’s influence extends to the fundamental human trait of trust. Studies have shown that oxytocin levels increase in response to intentional trust.

Administering intranasal oxytocin can increase interpersonal trust in humans, even in scenarios involving monetary stakes or the sharing of confidential information, without affecting non-social risk-taking. This effect is particularly pronounced within one’s own social group. Genetic variations in the oxytocin receptor gene are also linked to trusting behaviors.

The importance of social bonds becomes starkly evident in their absence. The loss of social relationships or chronic social isolation can lead to severe negative consequences for physical and mental health, including increased risk of cardiovascular disease, infectious diseases, and the development of depression and anxiety disorders.

Prairie voles serve as a powerful model for studying these effects: when separated from their bonded partners, they exhibit behaviors reminiscent of human grieving and bereavement, such as increased anxiety and passive stress-coping behaviors (e.g., immobility in forced swim tests).

This “depressive-like” state is associated with disruptions in the brain’s oxytocin system, including reduced oxytocin receptor binding in the nucleus accumbens. Intriguingly, these negative effects are mediated by the brain’s corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) system, which becomes activated following partner loss and negatively impacts oxytocin signaling.

While this physiological response may have evolved to encourage reunion and maintain long-term partnerships in the wild, it can become maladaptive when reunion is not possible. The good news is that in prairie voles, chronic local infusion of oxytocin into the nucleus accumbens can normalize depressive-like behaviors following partner separation, suggesting a potential therapeutic avenue.

These profound insights into oxytocin’s role have significant translational implications for developing new treatment strategies for human psychiatric conditions characterized by social impairments.

This includes disorders like autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and schizophrenia, where difficulties in forming or maintaining social bonds are core features. While oxytocin may not be a universal panacea, understanding its specific contributions to social selectivity, early bond formation, social reward, and stress buffering can guide more targeted pharmacological interventions.

Furthermore, research into stimulating endogenous oxytocin release could offer promising avenues for personalized medicine, particularly for individuals struggling with attachment difficulties due to genetic predispositions or early life social neglect.

Understanding the “Social Brain”: Why These Findings Matter

The collective body of research underscores that friendship is not merely a human construct but an evolved trait shared across many animal species. This concept is supported by the “social brain hypothesis,” which posits that the demands of group living drove the evolution of larger and more complex brains.

Key cognitive abilities underpin these social connections:

Individual Recognition:

The capacity to recognize and remember others as unique individuals, using cues like faces, vocalizations, or scents, is crucial. Humans, sheep, and even dolphins demonstrate remarkable long-term social memory.

Social Information Processing:

Animals, like humans, value social information, and specific brain areas (e.g., anterior cingulate cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens) are activated by social rewards.

Theory of Mind (ToM):

The ability to understand the intentions and mental states of others, even in rudimentary forms in non-human animals, helps navigate complex social challenges.

Oxytocin interacts with other vital neurochemicals like dopamine (involved in reward and social preference) and serotonin (modulating how individuals perceive and respond to social information) to orchestrate complex social behaviors.

Furthermore, research highlights fascinating social dynamics:

Homophily:

Friends often share similar characteristics, including age, social status, personalities, and even genetic profiles. Unrelated friends can be as genetically similar as fourth cousins, suggesting potential “indirect fitness benefits” through a form of kin selection.

Parental Influence:

In humans and other primates, parents play a role in shaping their offspring’s social networks, even introducing them to potential friends.

Ultimately, friendship confers significant adaptive benefits, linked to increased survival and reproductive success in various species. For humans, strong social relationships can increase longevity by 50%. Friendships help individuals cope with the challenges of group living, providing support, reducing harassment, and mediating the costs of competition.

While stress reduction is often associated with social bonding, it’s crucial to understand it as a proximate mechanism (how it works), rather than the ultimate reason (why it evolved) for friendship.

The complexities of cooperation within friendships, whether through direct reciprocity or “emotional bookkeeping” (basing interactions on attitudes rather than strict calculations), continue to be a rich area of scientific inquiry.

In the end

Oxytocin, far from being just the “love hormone,” plays a sophisticated and critical role in the intricate tapestry of our social and emotional lives. Recent research, particularly from prairie vole studies, emphasizes its unique importance in facilitating the rapid formation and selectivity of friendships. It influences who we choose to bond with, how we respond to strangers, and even our resilience to early life adversity.

By modulating neural circuits involved in social recognition, reward, and even aggression, oxytocin helps orchestrate the complex dance of social relationships. While it may not be the sole determinant of long-term romantic or parental bonds, its contribution to the initiation and quality of these connections, and its crucial role in buffering against the profound negative impacts of social loss and isolation, cannot be overstated.

Understanding the precise mechanisms of oxytocin and its interplay with other neurochemicals offers immense potential for developing targeted interventions to enhance social motivation and cognitive function across all age groups, especially for children and adults struggling with conditions that impair social connections. The ongoing exploration of this “social brain” continues to deepen our understanding of what it means to connect, to belong, and to thrive as deeply social beings.