A new study from Concordia University reveals that while babies are natural imitators, their earliest “overimitation” isn’t about making friends with robots (or even humans).

Key Takeaways

- Infants (16-21 months) showed low rates of overimitation of unnecessary actions.

- No link was found between infant overimitation and a general social affiliation preference.

- Elicited and unfulfilled intentions imitation tasks were significantly correlated.

- Social motivation for overimitation is suggested to emerge later in childhood.

- Task complexity and robot novelty might explain these early findings in infants.

- Adults should remember children mimic actions, even unnecessary ones, to foster critical thinking.

GANDHINAGAR: We all know kids love to imitate. From mimicking silly faces to attempting complex tasks, watching and copying others is a cornerstone of how children learn, acquire new skills, and soak up cultural knowledge.

But sometimes, this copying goes a step further, into something called overimitation: reproducing actions that aren’t actually necessary to achieve a goal. Think of a child tapping a box repeatedly before opening it, just as they saw an adult do, even though the taps do nothing to unlock the box.

This puzzling behavior is found across cultures and even persists into adulthood, suggesting a deeper psychological root.

For years, researchers have debated why we do it. Is it simply a cognitive shortcut, where we perceive all demonstrated actions as crucial? Or is it a deeply social act, driven by a desire to affiliate, to be part of the group, or to conform to social norms? Previous research often points to social reasons, showing that kids overimitate more when the model is familiar or part of their “in-group”. However, the exact mechanisms and how early this social link emerges have remained unclear.

Peeking into Baby Brains: The Concordia Experiment

To shed light on these questions, Marilyne Dragon and Diane Poulin-Dubois at Concordia University embarked on a groundbreaking study, focusing on a younger age group than typically examined: infants between 16 and 21 months old. Their goal was to see if overimitation was present at this early stage and, crucially, if it was already linked to a general desire for social affiliation.

They recruited 73 infants and had them participate in four distinct tasks designed to measure different types of imitation and social preference:

- The Overimitation Task: Infants watched an experimenter open a box containing a toy, using a sequence that included one causally irrelevant action (e.g., tapping the lid) along with two necessary ones. The infants then got a chance to open the box themselves, with researchers counting how many irrelevant actions they copied.

- The Elicited Imitation Task: This classic task assessed memory. Infants had to accurately recreate a sequence of three actions, like putting a teddy bear to bed with a pillow and blanket.

- The Unfulfilled Intentions Imitation Task: Here, the experimenter demonstrated an action (like separating a dumbbell) but deliberately failed to complete it. The infants were then given the materials and scored on whether they completed the intended action, testing their understanding of goals.

- The In-Group Preference Task: To measure social affiliation directly, infants watched a video of a woman and a robot simultaneously offering the same plush toy. Hidden behind a curtain, an experimenter then presented the actual toys, and infants’ first reach determined their preference for the “human” or “robot” agent.

Surprising Findings: Not So Social, Yet

The results offered some unexpected insights into the minds of these young learners.

- Low Overimitation: Only about 40.8% of the infants copied at least one irrelevant action, and the overall rate of overimitation was quite low. This suggests that while present, overimitation isn’t a dominant learning strategy for this age group.

- No Social Link: Crucially, the study found no association between overimitation and in-group preference. Infants didn’t show a clear preference for the toy offered by the human over the robot, indicating that their early overimitation wasn’t driven by a desire to affiliate with someone similar to them.

- Cognitive Ties: Interestingly, the elicited imitation and unfulfilled intentions tasks were significantly correlated. This suggests that these two forms of imitation, which both heavily rely on memory and understanding intentions, share a common cognitive basis.

- Age Matters for Some Imitation: Older infants in the 16-21 month range performed better on the elicited imitation task, indicating a developmental progression in complex action sequencing.

Why the Disconnect?

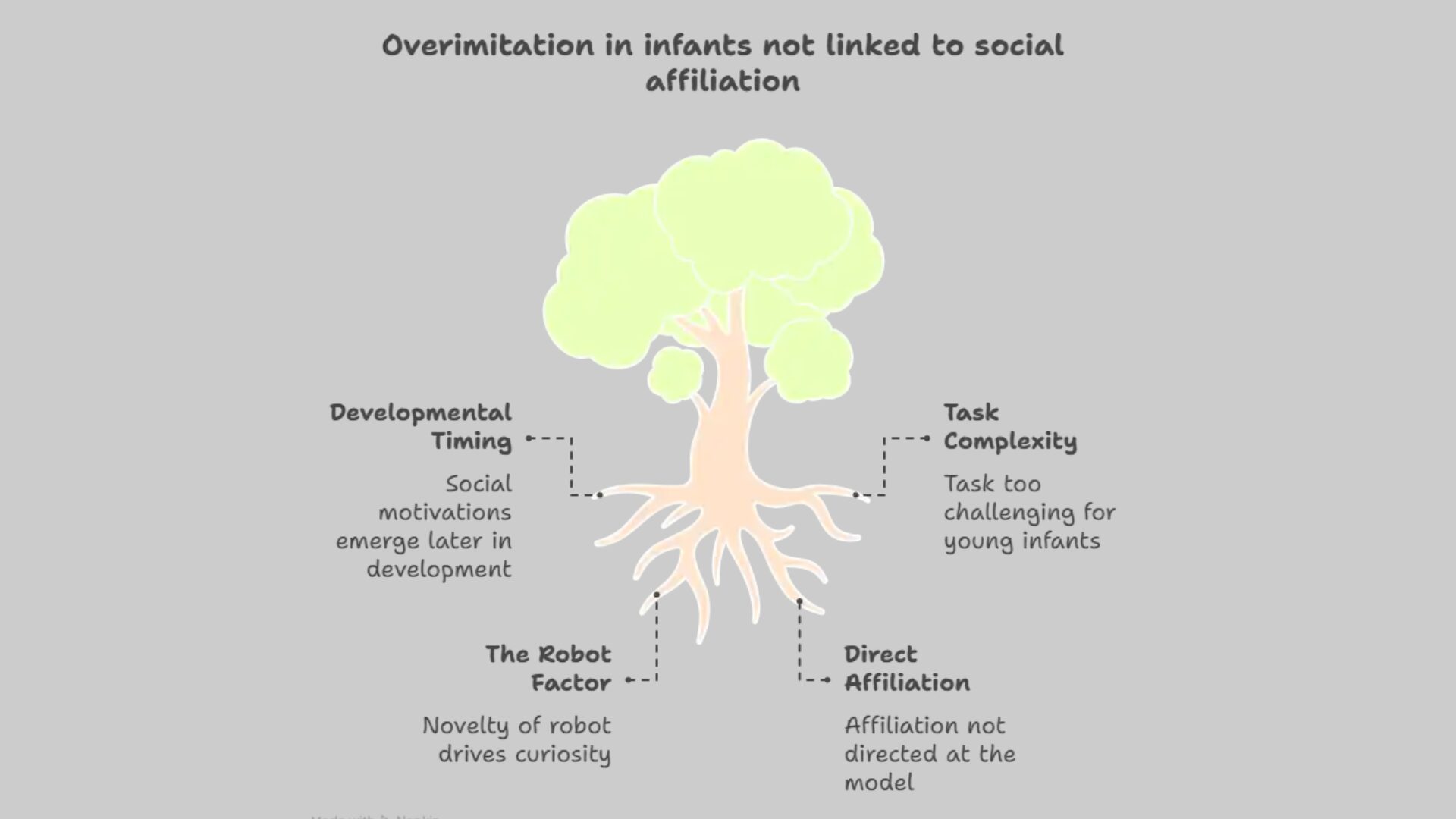

The lack of a link between overimitation and social affiliation in infancy prompts several interpretations:

- Developmental Timing: It’s possible that the social motivations behind overimitation emerge later. The 18-month mark might be a “transition period” where infants are moving from purely selective imitation (copying only functional actions) to more exact imitation (copying everything), but the social drive isn’t fully formed yet.

- Task Complexity: The overimitation task itself might have been too challenging for infants this young, especially with the irrelevant action placed in the middle of a three-step sequence. Most infants successfully copied the relevant actions, suggesting the issue wasn’t attention, but perhaps inhibitory control or understanding of the arbitrary action.

- The Robot Factor: For many infants, seeing a robot was a novel experience. This novelty might have made the robot particularly intriguing, leading infants to choose its toy out of curiosity rather than identifying it as an “out-group” member. Infants may not yet have developed a strong social preference for humans over robots, unlike, for instance, a preference for someone speaking their native language.

- Direct vs. General Affiliation: The study’s “in-group preference” task aimed for a broad measure of social affiliation. However, it might be that the link between overimitation and social affiliation only manifests when that affiliation is directed specifically at the model performing the actions, rather than a general preference for humans over robots.

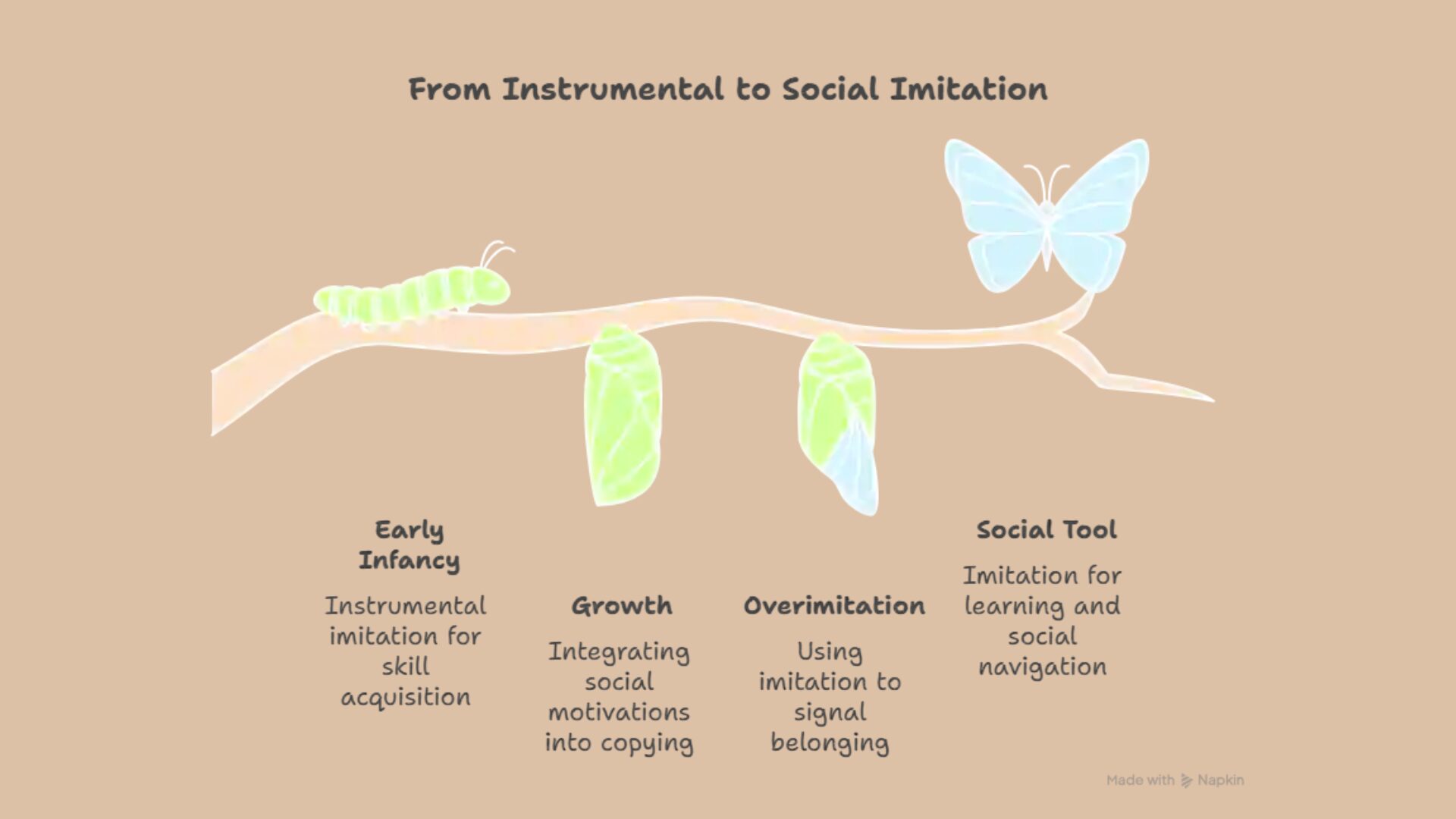

The Dual Nature of Learning: Instrumental vs. Social

This research shows that imitation isn’t a single, uniform process. It serves a dual function: sometimes it’s instrumental (purely for learning a skill), and other times it’s social (for building relationships). It appears that in early infancy, the instrumental aspect of imitation might be more prominent. As children grow, they likely integrate social motivations more deeply into their copying behaviors, using overimitation as a tool to signal belonging and desire for affiliation.

What’s Next for Our Little Imitators?

This study takes a vital step in understanding the developmental origins of overimitation. Researchers emphasize the need to continue exploring very young children. Future studies could simplify tasks, use more familiar models (like parents), or focus on more distinct social cues (like language or gender) in affiliation tasks to better understand when and how the social drive behind overimitation truly takes hold.

For parents and educators, the takeaway is clear: children are keen observers. “It is important for parents and teachers to be mindful that their children will imitate them,” notes lead author Marilyne Dragon. “They will mimic and copy actions that are not necessary, so that is something to keep in mind. We want children to develop critical thinking skills.” As children develop, their imitation becomes a powerful tool not just for learning, but for navigating their social world. Understanding this complex dance of copying helps us optimize their learning experiences from the very start.