🔑 Key Takeaways

- Universal school-based SEL programs work: They reduce early signs of antisocial behavior like aggression and conduct problems, though effects are modest.

- Lasting impact: Most studies show benefits that endure beyond the classroom, suggesting SEL programs create durable behavioral improvements.

- No harm, only gains: None of the reviewed studies found adverse effects from SEL programs.

- Gender differences remain unclear: Boys and girls benefit similarly overall, but future research should disaggregate results more consistently.

- Not a standalone fix: SEL programs are most effective when integrated into broader community and family-based strategies.

- Wider benefits: Beyond reducing aggression, SEL also improves emotional intelligence, prosocial skills, self-regulation, and academic performance.

- Policy implication: Schools can serve as critical hubs for early intervention, but collaboration across education, health, and justice systems is essential.

GANDHINAGAR: Walk into any school and you’ll see more than math tests and spelling quizzes at play. You’ll see kids struggling with anger, cliques forming in hallways, conflicts sparking in classrooms. For some, these tensions spill over into aggression, rule-breaking, or even brushes with the law later in life. Communities have long wrestled with how to stop this slide into antisocial behavior.

Parents and families often stand at the front lines. Many prevention programs focus on parenting skills and family support. But here’s the catch: the families who need the most help are often the hardest to reach. Mothers involved in the criminal justice system, for example, frequently keep to themselves. They fear judgment, pride themselves on self-reliance, and distrust outside support. Meanwhile, their children may act out more and more.

So where do we find another way in? Researchers increasingly point to a place that touches nearly every child: schools.

Unlike programs that target only “at-risk” kids, school-based initiatives can reach everyone. By teaching all students together, schools reduce stigma and deliver skills that benefit children across the board. And among these, Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) programs are gaining traction worldwide.

A team of researchers—Jared Muser (Griffith University, Australia), Tyson Whitten (UNSW Sydney and Griffith Criminology Institute, Australia), Josephine Virgara (Griffith University, Australia), Nadine Connell (Griffith University and Griffith Criminology Institute, Australia), and Stacy Tzoumakis (Griffith University, UNSW Sydney, and Griffith Criminology Institute, Australia)—decided to put SEL programs under a microscope. Their systematic review and meta-analysis, published in the International Journal of Behavioral Development, asked a sharp question: Do universal school-based SEL programs actually reduce early signs of antisocial behavior like aggression and conduct problems?

Their answer: yes, but with nuance.

What SEL Programs Actually Teach

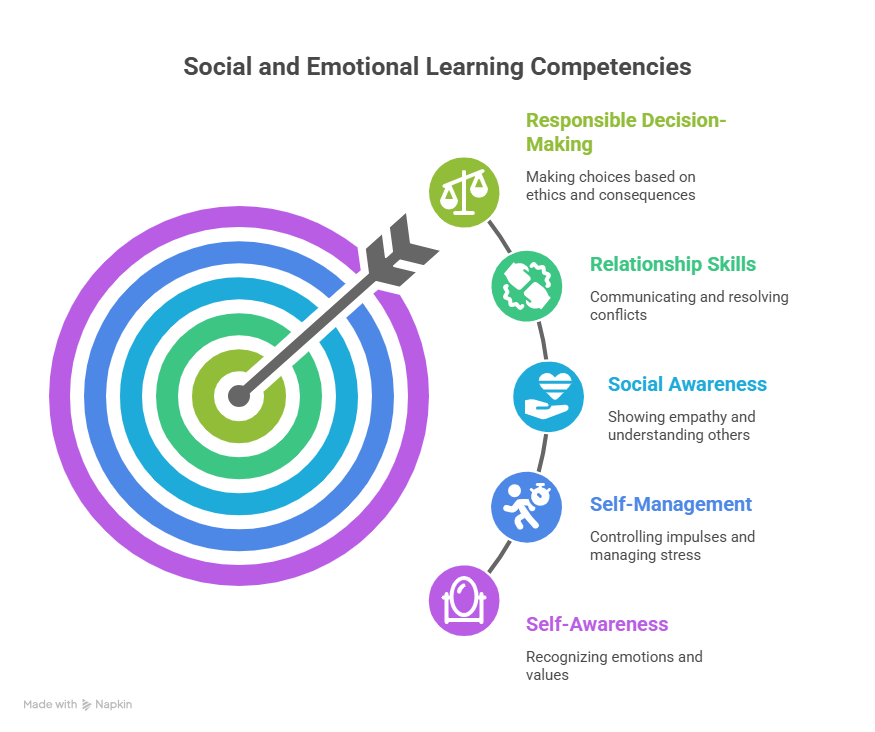

Before diving into the findings, it helps to understand what SEL is.

At its core, SEL equips students with skills to manage their emotions, build relationships, and make thoughtful choices. Think of it as the curriculum for how to be human, not just how to pass exams.

The leading framework, developed by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), highlights five key competencies:

- Self-awareness – recognizing one’s emotions, values, and strengths.

- Self-management – controlling impulses, managing stress, and setting goals.

- Social awareness – showing empathy and understanding others’ perspectives.

- Relationship skills – communicating, cooperating, resolving conflicts.

- Responsible decision-making – making choices based on ethics, safety, and consequences.

On the surface, SEL seems like it’s about “soft skills.” But the link to antisocial behavior is clear. A child who learns to manage anger won’t need to lash out. A teen who practices empathy is less likely to bully. A student who makes careful decisions won’t risk sliding into delinquency.

This makes SEL a strong candidate for preventing the early warning signs that often precede crime.

Why Early Intervention Matters

The earlier the intervention, the better the odds of changing life outcomes. Research has repeatedly shown that kids who show high levels of aggression or conduct problems in elementary school are more likely to face trouble later—ranging from juvenile delinquency to adult criminal behavior.

Take aggression: studies reveal that physical aggression in childhood often continues into adolescence. Similarly, conduct problems at ages 7 to 9 link to a host of future struggles, from crime and substance abuse to poor mental health.

If schools can teach children healthier ways to manage conflict and emotions before patterns set in, they might alter these long-term trajectories. That’s why Muser and colleagues turned their focus to SEL.

What the Study Looked At

The research team carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis, which means they sifted through thousands of studies to find high-quality evidence.

Here’s how they did it:

- They searched databases like PsycINFO and ERIC, reviewed top journals in psychology and prevention science, and combed Google Scholar.

- They looked for studies published between 2012 and 2023 that met strict criteria. Programs had to be universal (delivered to all students, not just at-risk groups), school-based, and implemented during school hours.

- Eligible studies had to focus on children from kindergarten through grade 12, use experimental or quasi-experimental designs, and report outcomes tied to antisocial behavior (aggression, conduct problems, delinquency).

They excluded studies focused solely on high-risk youth, mental health conditions, or outcomes like bullying, dating violence, or substance use. The goal was to zero in on precursors to delinquency—the early signals that a child might be on a risky path.

From an initial pool of 6,280 articles, the team narrowed down to 35 that fit their criteria. Together, these studies involved 48,437 students aged 4 to 17.

What They Found

So, do SEL programs work? The evidence points to yes—with caveats.

- Broad effectiveness: In 27 of the 35 studies, SEL programs reduced some form of antisocial behavior. Ten reported mixed results, while eight showed no clear benefit. Importantly, none showed harm.

- Lasting effects: Of the 12 studies that followed students beyond the program, 10 showed that improvements stuck over time.

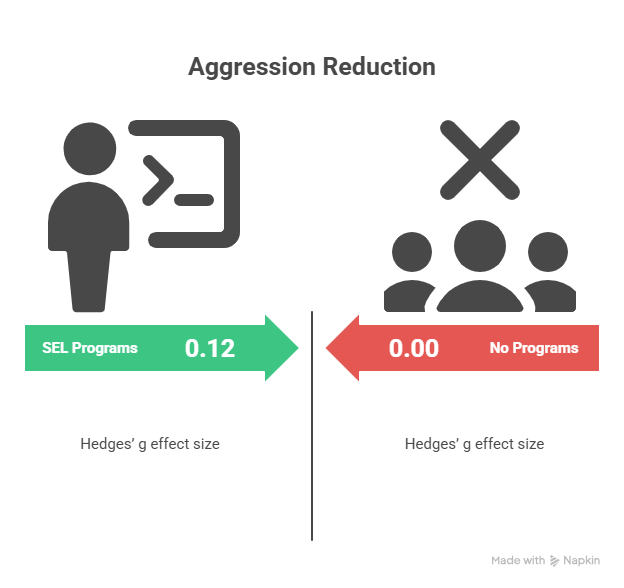

When the researchers ran their statistical analyses, they found small but significant effects:

- Conduct problems: A weak but positive effect (Hedges’ g = 0.09). Interestingly, results varied by country—programs in Italy showed stronger outcomes than those in the UK.

- Aggression: A similar weak but significant effect (Hedges’ g = 0.12). This effect held steady regardless of gender, age, reporter type, or country.

In plain language: SEL programs don’t erase aggression or conduct problems, but they nudge students in the right direction. And those nudges can add up.

The Gender Question

One of the study’s aims was to see if SEL programs work differently for boys and girls. The answer: not consistently.

Out of 17 studies that broke results down by gender, only six found differences. Four showed stronger effects for boys, two for girls. The meta-analysis as a whole found no significant gender differences.

This suggests SEL can help both boys and girls, though researchers argue future studies should keep reporting gendered outcomes. Without that data, it’s hard to know if certain groups benefit more.

What the Study Didn’t Answer

Like any research, this study had limits.

- Scope of behaviors: The team excluded bullying and dating violence, even though those overlap with aggression. They wanted a clean focus on early antisocial behavior, but it means the results don’t capture every relevant problem.

- Long-term impact: Few studies tracked students into late adolescence or adulthood. So while SEL helps in childhood, we don’t yet know how much it reduces crime years later.

- Implementation quality: The review didn’t explore how well schools delivered programs. A poorly run SEL initiative might not have the same impact as a high-quality one.

These gaps matter, because they remind us that SEL isn’t magic. It works best as part of a bigger picture.

Why SEL Still Matters

Despite modest effect sizes, the researchers argue SEL programs are valuable. Why? Because they do more than curb aggression.

Studies consistently show SEL boosts self-regulation, emotional intelligence, prosocial behavior, and even academic performance. In other words, SEL strengthens the very skills kids need to thrive—not just avoid trouble.

When you add up these benefits, SEL becomes a powerful tool in the broader effort to support healthy youth development.

What This Means for Schools and Communities

The big takeaway: SEL programs should be part of a wider strategy, not a stand-alone fix.

Preventing antisocial behavior is complex. It requires work at multiple levels—families, schools, communities, and policy. Universal SEL programs reach kids in classrooms, but they should complement:

- Family-based programs that help parents support their children.

- Targeted interventions for at-risk youth.

- Community partnerships involving education, social services, and health.

When combined, these efforts can reduce crime, improve mental health, and even cut government spending on justice and health systems.

A Final Word

The work of Muser, Whitten, Virgara, Connell, and Tzoumakis shows that schools can play a meaningful role in steering children away from antisocial paths. Universal SEL programs don’t solve everything, but they matter. They give children tools to manage anger, build empathy, and make better decisions—skills that ripple outward into safer, healthier communities.

As the researchers put it, schools aren’t just places for academics. They’re vital frontlines in the fight against youth antisocial behavior. And the evidence is clear: with SEL, schools can help.