GANDHINAGAR: So you’ve probably heard people joke about “mom brain”—that forgetful, slightly spacey mental fog new moms supposedly get. Maybe you’ve even seen memes about it. But what if we told you it’s not just a joke—and it’s definitely not just about moms?

Scientists are now discovering that becoming a parent actually rewires your brain. Like, for real. We’re talking MRI scans, hormone shifts, and changes so deep that your brain actually looks different. And yes—this happens to dads too. So, what’s really going on in your brain when you become a parent, and why this science might just change how society supports moms, dads, and families in general.

🔬 First Up: Your Brain Physically Changes When You Have a Baby

For years, the term “mommy brain” has been tossed around, often with a dismissive or even negative connotation, implying new mothers become forgetful or less sharp. However, the research of Dr. Darby Saxbe, PhD, Professor of Psychology at the University of Southern California, building on emerging neuroscience literature, reveals a far more intricate and, surprisingly, adaptive story. She explains that parenthood leads to a profound remodeling of the brain. This isn’t just a human phenomenon; scientists have observed similar changes in rodents and primates, linked to adaptations that support the nurturing of a new infant.

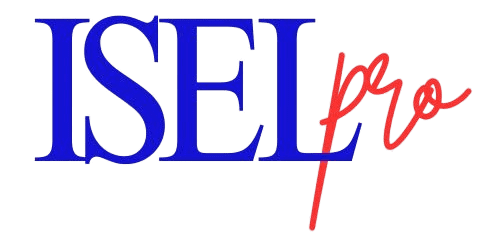

The pivotal moment in this research came in 2016 with a study from a Spanish research group. They longitudinally tracked mothers, scanning their brains before pregnancy and then again a few months after birth. What they discovered might sound alarming at first: the brain actually got smaller, losing some gray matter volume. But Dr. Saxbe clarifies that this isn’t a bad thing.

Instead, it’s believed to be a process of streamlining, making the brain more efficient, especially when it comes to the intense social information processing required of new parents. Think of it like a computer optimizing its hard drive, cutting out unnecessary files to run faster.

The areas where moms lost brain volume were specifically linked to “mentalizing” and “social cognition” – skills crucial for understanding and responding to others. And here’s the kicker: moms who lost more brain volume in these areas reported stronger bonds with their infants. Far from making them “less smart,” this brain reorganization seems to enhance a mother’s ability to connect with her baby.

👶 Dads, You’re Not Off the Hook—Your Brain Changes Too

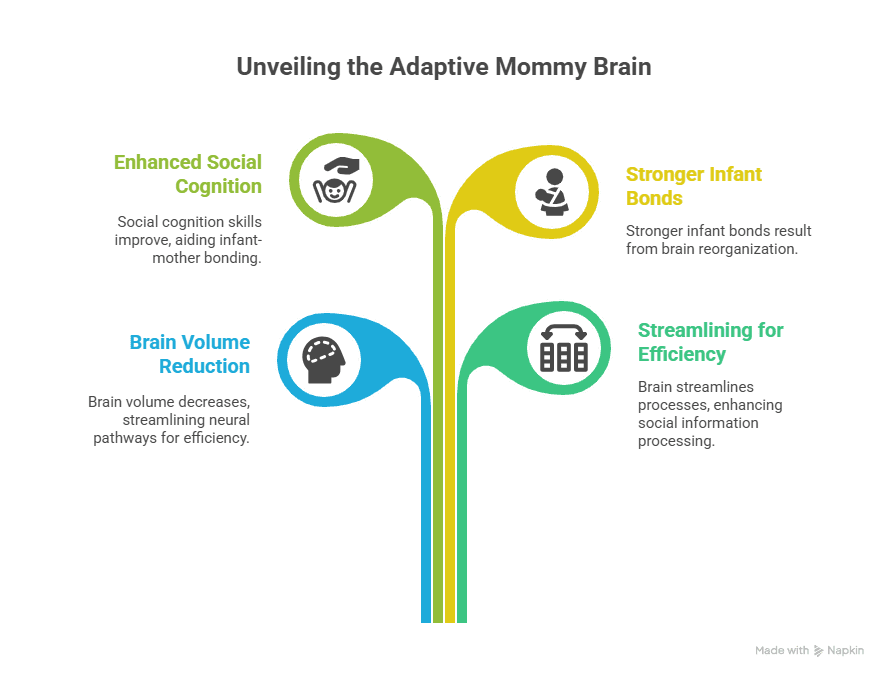

While the “mommy brain” concept had some cultural recognition, the idea that fathers’ brains also undergo significant changes was much less explored. This is where Dr. Saxbe’s work truly shines. Around the same time the Spanish study on mothers was published, Dr. Saxbe’s lab in California was collecting its own data, recruiting couples expecting their first child and scanning the men during mid-pregnancy and again about six months postpartum.

Recognizing the immense potential for collaboration, Dr. Saxbe secured a Fulbright scholarship and traveled to Spain to work with the group that studied mothers. By combining her initial sample of 20 dads with 20 dads from the Spanish study, a remarkable finding emerged: men also experienced brain changes that were strikingly similar to those observed in mothers.

However, there were a few key differences. The changes in fathers were more subtle, less striking, and less significant. For instance, a machine learning algorithm could accurately tell if a mom was pre or postpartum based solely on her brain structure, but the effects weren’t as pronounced for dads.

Another interesting distinction lay in the affected brain regions. In mothers, changes were seen in both the cortex (the outer layer involved in higher-order thinking) and the subcortex (the “lizard brain” responsible for more primal functions and emotion processing, including the amygdala). For fathers, however, changes were observed only in the cortex. Dr. Saxbe has since replicated these findings in her own lab with a larger sample of fathers, linking these cortical changes to parenting measures and other behavioral insights.

A critical question naturally arises: are these brain changes permanent? For mothers, the Spanish group did a follow-up seven years later, finding some retention of the gray matter losses, although areas like the hippocampus showed some rebound. Overall, the brain remained “a little bit smaller, or I like to say leaner and meaner, than it was before pregnancy”.

Dr. Saxbe’s team is now conducting a 7-year follow-up study on the fathers in her sample, hoping to provide more definitive answers about the long-term effects in men. The journey of parenthood is a complex, evolving one, and the scientific community is just beginning to map its neurobiological landscape. What happens with subsequent births, for example, is still an open question, due to the emerging and relatively small nature of this field.

🔄 Hormones: Not Just a “Girl Thing”

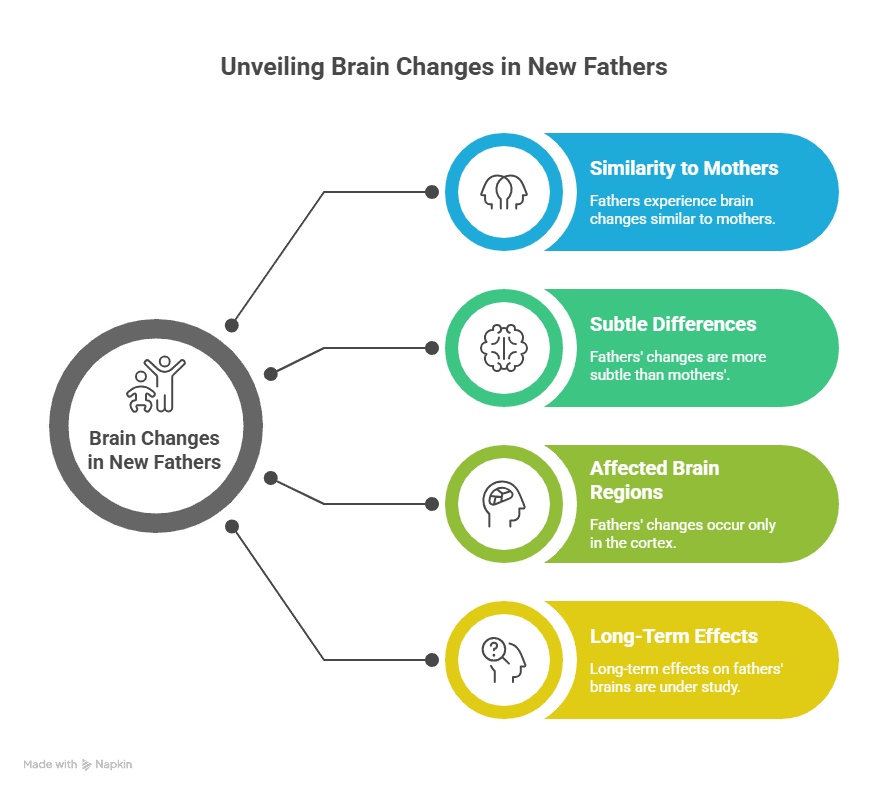

Beyond structural brain changes, Dr. Saxbe’s research also sheds light on the hormonal shifts that occur in new fathers. While we often associate hormones in parenthood with pregnancy and birth, there’s compelling evidence of hormonal changes in men as well. The hormone that has been most extensively studied in fathers is testosterone, commonly linked with power, status, and dominance.

In biparental animals like rodents and primates, testosterone levels are known to drop around the birth of offspring. Fascinatingly, the same pattern appears in humans. A landmark study by Lee Gettler at the University of Notre Dame, conducted in the Philippines, tracked men longitudinally, measuring their testosterone in their 20s and then again years later.

The study found that men who were living with children, particularly those spending more time caring for them, had lower testosterone. Crucially, this longitudinal data helped answer the “chicken or egg” question: men who became fathers actually had higher testosterone levels before becoming dads and then showed a significant decline. This strongly suggests that fatherhood itself triggers these hormonal changes.

Dr. Saxbe’s lab has replicated these findings, observing that lower testosterone and a drop in testosterone in fathers are linked with a greater motivation to participate in baby care and better relationship quality across the transition to parenthood. These hormonal shifts appear to be highly adaptive, helping fathers engage more deeply in nurturing their infants.

The hormonal interplay extends to partners as well. Dr. Saxbe’s research revealed that when dads had lower testosterone around nine months postpartum, they reported more depression themselves. However, their female partners actually reported less depression when they were with these lower-testosterone men.

This intriguing dynamic, which Dr. Saxbe describes as a “good for the goose, not good for the gander” situation, suggests a complex interplay where a dad’s hormonal shift, while adaptive for the family unit, might carry some mental health risks for the father that warrant further understanding. Interestingly, this positive effect for moms was entirely “mediated by relationship satisfaction”.

This implies that a new mom with a partner whose testosterone is adaptively dropping might experience a better co-parenting relationship, providing a buffer against postpartum depression. Dr. Saxbe emphasizes, though, that there’s a “happy medium” – most men fall into a range where these hormonal changes are largely adaptive and don’t necessarily lead to poor mental health.

And what about the common concern regarding sex drive? Dr. Saxbe acknowledges that the transition to parenthood significantly reorganizes a couple’s sexual activity due to practical limitations and changes in desire.

A temporary drop in sex drive, from an evolutionary perspective, might not be detrimental. It represents a trade-off between “mating” and “parenting” strategies: a shift from maximizing reproduction opportunities to investing heavily in the care and survival of existing offspring. In stable, industrialized societies, focusing on intensive investment in a few children becomes more adaptive than having many, which aligns with observed smaller family sizes.

Beyond Brain Scans: Sleep, Cognition, and Lifelong Benefits

While brain structure and hormones are central, Dr. Saxbe’s research also considers other factors that play a role in the parental transition. Sleep deprivation, a universally acknowledged reality for new parents, is often assumed to be the cause of any cognitive or mental changes. However, Dr. Saxbe’s lab found that while dads with more gray matter volume reduction did report worse sleep, it appears the sleep issues are a consequence rather than the cause of the brain changes. When parents become more motivated and engaged in caregiving, they naturally experience more disturbed sleep because they’re frequently getting up with the baby.

The “mommy brain” narrative often focuses on forgetfulness. Dr. Saxbe points to a growing body of literature suggesting that rather than becoming “less smart,” mothers actually sharpen their cognitive functioning in specific ways. They gain an enhanced ability to remember and retrieve information specific to their infant. This makes evolutionary sense; for a rodent, remembering where her pups are is crucial for survival. While humans don’t typically “smell our babies who have left the premises,” we do need to process a vast amount of information about our infants and be highly responsive to their cues. So, it’s not that parents are becoming more forgetful in general, but rather that they are monitoring more infant-specific information, potentially at the expense of less crucial, non-baby-related details. Dr. Saxbe suspects similar cognitive shifts occur in fathers who actively engage in caregiving.

Perhaps one of the most exciting long-term implications of this research is the idea that parenthood might be “neuroprotective” in late life. Large data sources, like the UK Biobank, are linking the number of children a person has with markers of what is considered a “younger looking brain”. This holds true for both men and women, suggesting it’s not just about pregnancy hormones, but the caregiving experience itself. Whatever intricate processes unfold in the brain during early parenthood, they seem to confer long-term benefits for brain health.

Parenthood as a “Window of Neuroplasticity”

Dr. Saxbe conceptualizes the transition to parenthood as a “third window of enhanced neuroplasticity”. Think about it: our brains undergo massive growth and remodeling during infancy and early childhood (your first window).

Then, adolescence marks a second major period of neural remodeling, where the brain adapts for individuation and forming peer relationships. Parenthood, Dr. Saxbe argues, represents another significant developmental window where the brain demonstrates remarkable adaptability.

The magnitude of brain changes during pregnancy and early postpartum has even been found to be similar to those seen during adolescence. This makes evolutionary sense: just as adolescents must learn a new repertoire of behaviors for independence, new parents must acquire a whole new set of skills and derive reward from nurturing to ensure the survival and well-being of their offspring. There’s also emerging recognition of further plasticity around aging, particularly for women during menopause, highlighting other times when hormonal shifts coincide with brain changes.

The Real-World Impact: Paternity Leave and Policy

Dr. Saxbe’s research isn’t just about understanding the brain; it has profound public policy implications. One significant area she’s explored is the impact of paternal leave, not only on dads but crucially, on moms and the family as a whole. Her lab, located in California, was fortunate to study this because the state offers a disability leave option for fathers.

Her findings are compelling: dads who had access to paid paternity leave showed better trajectories for sleep and stress. But the benefits for mothers were even more substantial: they experienced better trajectories of depression, were less likely to develop postpartum depression, were less stressed, and had better sleep across the transition to parenthood.

As Dr. Saxbe puts it, paternity leave is “one of those things that really benefits not just dads, but the whole family”. It benefits kids, partners, and acts as a crucial stress reliever for the entire family system. This research strongly supports the implementation of paid leave policies for all parents, drawing lessons from other industrialized countries that have successfully implemented generous family leave programs.

Dr. Saxbe frequently emphasizes the disconnect between political rhetoric and actual policy in the US. While there might be “pronatal” talk about wanting more babies, this isn’t coupled with policies that truly support healthy parenting. The US stands out among industrialized nations for its lack of universal paid family leave. It’s a staggering statistic that about a quarter of mothers in the US return to work within two weeks of giving birth, a reality Dr. Saxbe calls “complete insanity”.

She advocates for a fundamental shift in perspective: children are a “public good”. Moving away from an “individualistic framework” where raising kids is solely a personal choice and burden, she argues that “we all benefit from having healthy, happy kids who are growing and thriving,” because they are the future workforce, national security, and caregivers for the elderly. Recognizing kids as a public good can unlock the political will needed to implement policies that truly support families during this transformative period.

Challenging the “Intensive Parenting” Trap

Beyond policy, Dr. Saxbe’s work also critiques prevailing cultural norms around parenting. She recently wrote an op-ed in The New York Times about “underparenting” – the idea that giving kids more space, including time to be bored, benefits both children and parents. As a self-proclaimed “extremely lazy mom,” her personal experience intertwines with her research on parental stress.

She argues that the “intensive style of parenthood” that has become dominant in recent decades is a significant source of parental stress and might even be contributing to declining birth rates. This modern parenting approach is “very effortful,” “always on,” and “very child-centered,” involving constant shuttling to activities and curated experiences. Historically, this is unusual; in many cultures, children learn by modeling adults and contributing to the community, rather than being the constant focus of organized activities.

Time diary trends from the 1950s to today shockingly reveal that both mothers and fathers actually spend more time with their children now than they did in the “golden age” of doting 1950s motherhood. This intense, curated approach, Dr. Saxbe suggests, often hinders children’s access to unstructured play, which she believes is the “central way that kids learn in childhood”. Her work encourages parents to relax, enjoy their children more, and reconsider the unsustainable expectations often placed on them.

The Scientist’s Journey and Future Horizons

Dr. Darby Saxbe’s journey into this research field is rooted in a deep personal fascination with families and parenthood, stemming from her own experiences with her parents’ divorce. Like many psychologists, her “me-search” aims to understand and potentially improve aspects of life. As a graduate student, she was captivated by observing family life and the stressors parents faced. She realized that to truly make things better, one must go back to the origin – the formation of the family unit – to prevent stress and adversity before they arise. Her interest lies in the “adult side of the equation,” recognizing that “if you don’t have good healthy parents, you don’t have good healthy kids, and then it affects the whole society”.

This cutting-edge field of research is still young and evolving. Dr. Saxbe and her team are currently engaged in a 7-year follow-up study. They are bringing the families originally recruited during pregnancy back to the lab, where the children are now six and seven years old. The goal is to investigate how prenatal stress and adaptation during the transition to parenthood impact child outcomes in middle childhood. They are observing families in interactive activities, like building towers with blocks and using an Etch A Sketch, to study joint play and attention. They are also engaging parents in discussions about their child’s development and the division of labor within the household, revisiting some of the same themes from the initial study.

In addition to her ongoing research, Dr. Saxbe is eagerly anticipating the release of her book, “Dad Brain,” in spring 2026. She describes the writing process as a “delight” – a chance to tell stories without the rigid constraints of scientific articles. She’s already started on her second book, which will delve deeper into the “underparenting” concept, offering guidance on how parents can relax and enjoy their kids more, rather than succumbing to the pressures of “helicopter parenting”.

Dr. Saxbe’s work is a powerful reminder that becoming a parent is one of the most profound developmental experiences in adulthood, triggering complex biological and psychological changes that reshape individuals and families. By intelligently dissecting the science behind “Dad Brain” and “Mom Brain,” and advocating for policies that genuinely support families, Dr. Saxbe is not only deepening our understanding of human development but also laying the groundwork for a future where both parents and children can truly thrive. It’s an intelligent, sharp look at a topic that touches everyone, highlighting that the journey of parenthood is a dynamic, brain-changing adventure, full of both challenges and incredible opportunities for growth.

RESEARCH CITATIONS

https://www.apa.org/news/podcasts/speaking-of-psychology/dad-brain