GANDHINAGAR — In a quiet corner of India’s capital Delhi, a primary school in Dwarka area is reimagining learning by anchoring it in the languages children already speak.

This experiment is subtle, slow-moving, yet deeply disruptive. ITL Public School’s, principal Dr Sudha Acharya, is sowing the concept of multilingualism into the structure of primary education.

Unlike token “language celebration days” , ITL’s model is strategic, low-cost, and rooted in community participation. Dr Acharya, in a recent interview to CBSE HQ channel describes it as education’s “most overlooked assets: the linguistic diversity of its students.”

This is the anatomy of a language-based transformation—one guided less by slogans and more by systems thinking.

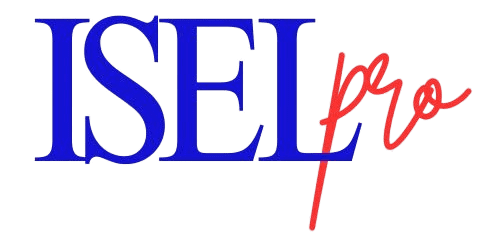

PHASE I: Mapping the Linguistic Terrain

Before implementing change, the school turned inward. It began by conducting a rigorous language mapping study—an unusual move in Indian schools, especially at the primary level.

Strategy 1: A Bilingual Survey That Did More Than Ask Questions

The leadership team, through a bilingual Google Form, asked families precise, practical questions: Which languages does your child speak comfortably? What’s spoken with grandparents? Could you contribute to school activities?

It was an attempt to profile students as multilingual individuals, not just learners of English or Hindi.

Strategy 2: Personalized Outreach to Ensure Inclusive Response

Teachers followed up on survey links with personal WhatsApp messages—often sent in Hindi or regional languages. Instructional videos accompanied the form, helping non-English-speaking parents participate meaningfully.

The outcome was revealing. Families reported speaking over 21 languages—from Bhojpuri and Dogri to Konkani and Nepali. Even children from support staff families had distinct linguistic identities—data that now informs classroom interactions.

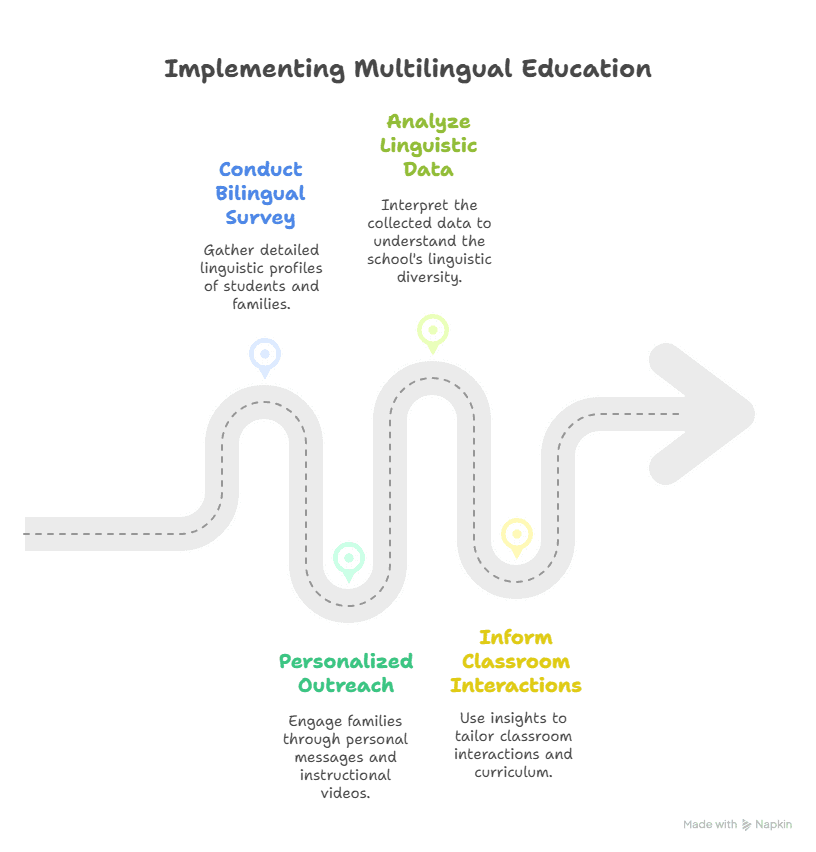

PHASE II: Securing Faculty Ownership

The most significant internal shift was cultural: moving teachers from passive implementers to active co-designers of a multilingual curriculum.

Strategy 3: Orientation Through Story, Not Instruction

Instead of conventional training, Dr. Acharya’s team facilitated dialogue-based workshops. Teachers shared their own linguistic journeys, family idioms, and regional stories.

What emerged was recognition: teachers’ own languages were relevant—not just the standard curriculum.

Strategy 4: Encouraging Interdisciplinary Crossovers

Departments began embedding regional and linguistic links into subject matter:

- Geography teachers introduced rivers through local myths.

- History teachers told resistance stories in native tongues.

- Biology classes included traditional herbal knowledge from tribal communities.

Faculty generated vocabulary posters, bilingual labels, and even created rotating “language flashcards” for use during lessons. The staffroom began to look more like a cultural lab than an office.

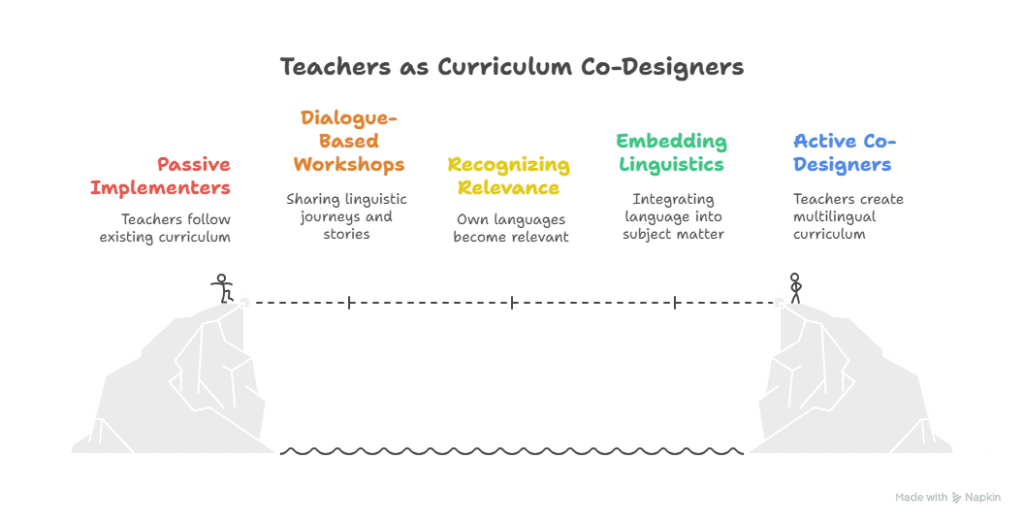

PHASE III: Enlisting Parents as Partners

Any shift in language policy risks pushback—especially in urban India, where English is aspirational. ITL tackled this with transparent data and inclusive messaging.

Strategy 5: Data Visualization to Frame the Narrative

At parent orientation sessions, pie charts showing the linguistic diversity of classrooms were displayed. It was to say: “We’re already multilingual. Let’s work with it.”

English wasn’t sidelined. Instead, multilingualism was framed as a cognitive and cultural advantage.

Strategy 6: Tapping Community Expertise

Parents were asked to contribute—not as guests, but as resources:

- A Marathi-speaking doctor ran a session on health practices.

- A grandmother sang folk lullabies in Malayalam.

- An artist helped students draw traditional Bengali Alpana patterns.

These interactions were more than cultural tokens. They were integrated into academic learning—like introducing regional food science during Onam week or linking math patterns to temple architecture.

Strategy 7: WhatsApp Groups for Real-Time Micro-Collaboration

The school created grade-wise, language-specific parent groups—Class 4 Odia families, Class 3 Tamil speakers, and so on. These became a library for idioms, pronunciation help, and folk tales.

PHASE IV: Building Student Ownership

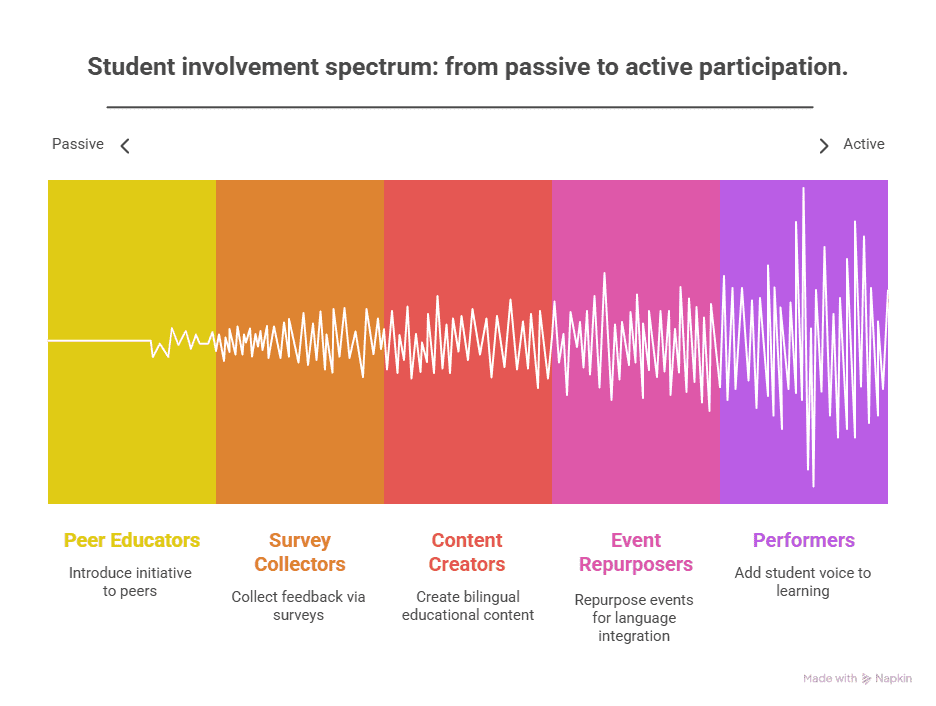

For any initiative to last, it must outlive the adult enthusiasm. ITL brought students to the center—not as consumers, but as co-creators.

Strategy 8: Peer Educators and Multilingual Content Creators

Student leaders were trained to:

- Introduce the initiative to peers

- Collect feedback via surveys

- Create bilingual educational content like infographics and word walls

In one instance, Class 4 students learning about states of matter translated “solid,” “liquid,” and “gas” into ten languages, including Sindhi and Nepali.

Strategy 9: Cultural Content with Language at the Core

Events like the Summer Drink Festival were repurposed for language integration. Students described coolers like Panakam or Solkadhi in English—but used regional vocabulary to emphasize code-switching.

Street plays, flash mobs, and podcasts added student voice—literally and metaphorically—to the learning ecosystem.

PHASE V: Curriculum as the Carrier, Not the Obstacle

To ensure sustainability, multilingual strategies were embedded into curriculum design.

Strategy 10: Monthly Language Themes Tied to Academic Content

Each month focused on one language:

- April (Odia): Math classes studied temple symmetry using Konark examples

- August (Malayalam): Science explored Ayurveda through traditional herbs

- December (Kannada): History classes studied resistance movements in South India using native ballads

Strategy 11: Visual Anchors to Normalize Multilingualism

Every classroom built its own “language tree,” with common greetings, gratitude phrases, and cultural facts in students’ home languages.

A Marathi-speaking child who had never spoken in class lit up when her phrase “Paay laagtu” appeared on the tree. She began teaching others how to say it.

PHASE VI: Institutionalizing Reflection and Replication

To prevent backsliding into English-only norms, ITL included review and evolution.

Strategy 12: Monthly Feedback Loops

Regular “reflection circles” gathered feedback from students, parents, and staff. This led to innovations like:

- Multilingual spelling bees

- Parent–child language journals

- Student-led dictionaries of idioms

Strategy 13: Open-Source Documentation

A digital repository of templates, lesson plans, flashcards, and session guides is under development—meant for use by other schools looking to replicate the model.

What Changed? Learning Became Local, and Therefore Deeper

Cognitive Gains: Students understood science and math better when introduced in familiar terms.

Participation Uptick: Students who previously stayed silent began contributing—especially when their languages were visible.

Trust Rebuilt: Parents who once viewed school as alien began to see it as an extension of home.

Bias Reduced: Students across caste and class lines began exchanging cultural terms, reducing prejudice and widening empathy.

In The End

There’s no grand tech investment here. No private ed-tech partnership. No pilot funded by an international foundation. The ITL model is simple, systemic, and striking: it uses what’s already present—students’ mother tongues, family customs, community knowledge—and integrates them into everyday schooling.

Dr. Acharya reflects, “This isn’t about revivalism. It’s about recognition. Language is not just a medium of instruction. It’s the medium of identity.”

In an era where education reforms often come with price tags and policies, ITL’s quiet shift offers a different lesson: real change starts with asking a child, “What language do you dream in?”—and then building the curriculum from there.