🔑Key Takeaways

- Autistic young adults face a paradox: despite high educational attainment (86% with postsecondary degrees), 57% remain unemployed and 71% rely on financial support.

- Emotional intelligence plays a central role in navigating postsecondary life, with strengths in self-awareness but struggles in real-time emotional regulation.

- Masking and internalized stigma drain emotional energy, leading to burnout and fragmented identity.

- Self-advocacy skills are rarely taught proactively, forcing many autistic individuals to learn them only during crises.

- Critical Disability Theory and the Neurodiversity Paradigm shift the focus from “fixing” individuals to dismantling systemic barriers and valuing diversity.

- Bliss recommends four changes for educators and policymakers:

- Create safe spaces that disrupt stigma and reduce masking.

- Redefine success around individual strengths, not just financial independence.

- Teach self-advocacy as a core civic skill from an early age.

- Make transition planning student-centered, with project-based and collaborative approaches.

- The study underscores that autistic individuals are not lacking empathy or insight; they need supportive systems that validate identity and nurture emotional growth.

GANDHINAGAR: Imagine this: a young autistic student works hard, excels in academics, and graduates with a university degree. On paper, they look set for success. But when they step into the world of work, they hit barrier after barrier—interviews that go nowhere, workplaces that don’t make room for their needs, colleagues who treat them well once they disclose their diagnosis. Despite being qualified and capable, they remain unemployed or underemployed.

This isn’t a rare story. It’s the reality for many autistic young adults today. Their participation in higher education and the job market lags far behind their non-disabled peers, even though they often have the skills and drive to succeed. Something is broken in the system—and a groundbreaking new study is showing us where to look for answers.

That study comes from Olivia F. Bliss, a researcher from Antioch University, whose doctoral dissertation takes a fresh approach: what if emotional intelligence (EQ)—the ability to understand, regulate, and use emotions—plays a much bigger role in autistic success than we’ve realized?

Her work, “Empowering Futures Together: The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Postsecondary Outcomes for Young Adults with Autism,” brings autistic voices in the US into the research process itself, something that’s been missing from much of the academic literature so far. And what she found is both eye-opening and deeply hopeful.

The Growing Need: Autism Rates Are Rising, Support Isn’t

Let’s start with the backdrop. Autism diagnoses have been increasing dramatically over the past few decades—a 316% rise in the US between people born in 1994 and today. That means tens of thousands of young autistic people are now entering adulthood, college, and the workforce. But while diagnoses have gone up, support systems haven’t kept pace.

We know that social and emotional learning (SEL)—teaching students skills like self-awareness, empathy, and communication—boosts outcomes in schools. But research on how emotional intelligence shapes life after high school for autistic young adults has been thin. Bliss set out to fill that gap.

A Different Kind of Research: Autistic Voices Front and Center

Most autism research has traditionally been done about autistic people, not with them. Bliss flipped that script by using something called Participatory Action Research (PAR).

Here’s what that means: instead of treating autistic individuals as subjects to be studied, Bliss made them co-researchers. They helped shape the questions, interpret findings, and ensure the research reflected lived experiences rather than outside assumptions.

This is important because research can sometimes fall into what scholars call “damage-centered” thinking—focusing only on what autistic people “lack” instead of their strengths and needs. By involving autistic voices directly, Bliss avoided that trap.

Her study worked in two stages:

- Quantitative phase – Participants completed the Six Seconds Emotional Intelligence Assessment (SEI), a well-regarded tool that measures different aspects of EQ. They also filled out demographic surveys about their postsecondary experiences.

- Qualitative phase – Using the survey results as a guide, Bliss held in-depth interviews and focus groups. This allowed participants to tell their stories in their own words, highlighting not just numbers but real human experiences.

The co-researchers were seven autistic adults, aged 24 to 30, all of whom had received specialized education services in high school. This age range was deliberate—it gave enough time for them to reflect on their journeys while keeping their transition to adulthood fresh in memory.

The Paradox: Degrees Without Jobs

One of the study’s most striking findings is a painful paradox.

On one hand, the participants were academically accomplished. Nearly 86% had completed a postsecondary degree, far above the Massachusetts state average of 18%.

But when it came to jobs, the picture looked bleak:

- 57% were unemployed, much higher than the national disability unemployment rate of 8.5%.

- Of those who were employed, only 42% held competitive jobs.

- Only one participant was earning enough to live independently without financial help.

- 71% relied on financial support from family or partners to get by.

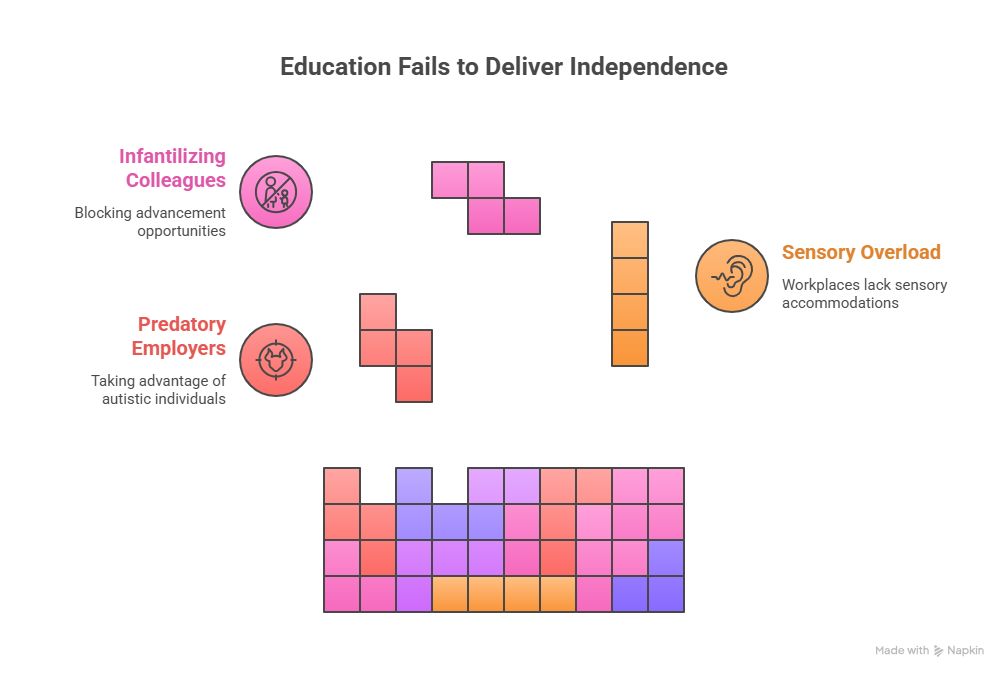

So here’s the problem: education is not translating into meaningful employment or independence. The reasons aren’t about laziness or lack of skill. Instead, participants described facing systemic barriers:

- Predatory employers who took advantage of them.

- Workplaces with no sensory accommodations (like fluorescent lights or noisy environments that can be overwhelming).

- Colleagues who infantilized them once they disclosed their autism, making advancement impossible.

This disconnect shows that while autistic individuals may achieve academically, they still encounter structural and interpersonal hurdles that block economic stability and personal fulfillment.

Emotional Intelligence: Strengths and Struggles

Now let’s talk about the heart of Bliss’s research—emotional intelligence.

Emotional intelligence (EQ) is often broken down into three big domains:

- Know Yourself – self-awareness; recognizing your own emotions and patterns.

- Choose Yourself – self-management; handling emotions and making decisions in the moment.

- Give Yourself – empathy and purpose; connecting with others and pursuing meaningful goals.

Here’s what Bliss found in her participants’ EQ profiles:

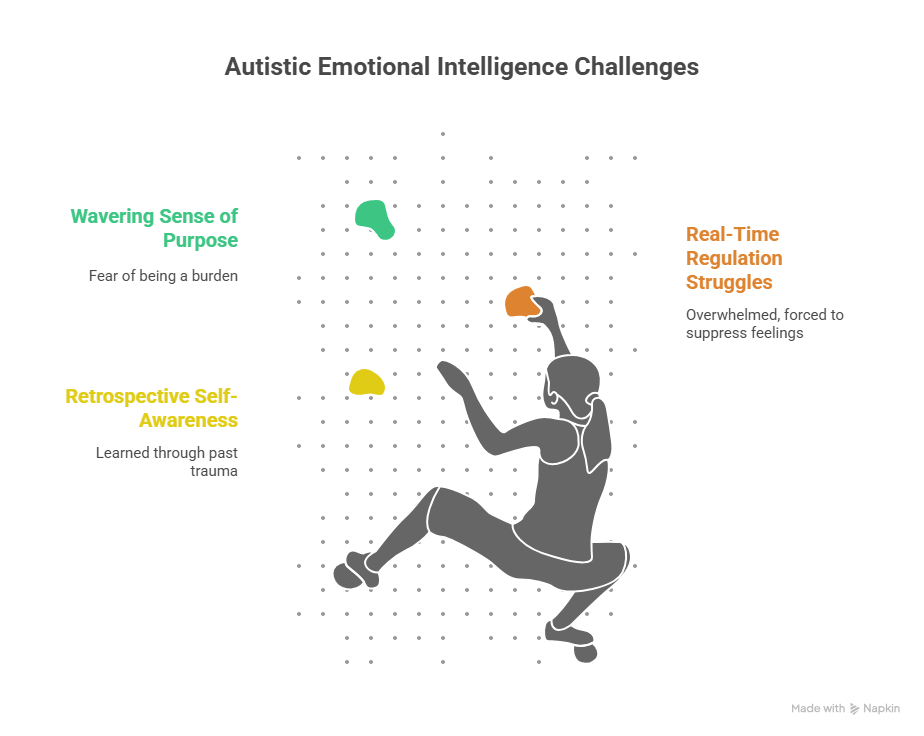

1. Know Yourself – Strong Awareness, But Learned Through Pain

Participants scored highest in this area. They were good at recognizing patterns and thinking through consequences. But there’s a catch: this awareness often came retrospectively, after they had already gone through exclusion, trauma, or burnout. In other words, they learned about their emotions the hard way, not because the system supported them.

2. Choose Yourself – Struggles With Real-Time Regulation

This was the hardest area. Participants often had trouble managing emotions in the moment. The lowest score across the board came in navigating emotions, with many describing feeling overwhelmed or forced to suppress their feelings.

A common strategy was masking—hiding autistic traits to blend in socially. While masking sometimes made life smoother in the short term, it led to exhaustion, anxiety, and even identity crises in the long run.

3. Give Yourself – Empathy Present, But Purpose Wavers

Contrary to harmful stereotypes, participants showed strong empathy. What varied was their sense of purpose and motivation. Many described putting others’ needs above their own, often because they feared being a burden. Over time, this drained their energy and left them disconnected from their own goals.

The takeaway? Autistic individuals aren’t lacking in empathy or insight. But without supportive environments, their emotional intelligence often develops in reactive, painful ways instead of being nurtured proactively.

The Toll: Stigma, Masking, and the “Autism Silo”

The qualitative interviews painted an even deeper picture. Participants described growing up in a society that framed autism as a deficit. They internalized stigma, feeling pressure to silence themselves, hide their differences, or constantly prove they weren’t a burden.

Over time, many retreated into what they called the “autism silo”—sticking mostly to neurodivergent peers. While this gave them comfort and understanding, it also reinforced feelings of being “separate” from mainstream society.

Another recurring theme was self-advocacy. Very few participants had been taught to advocate for their needs proactively. Instead, they only learned to speak up when they reached crisis points—when burnout or breakdown forced them to.

Rethinking Success: A Transformative SEL Approach

Bliss doesn’t just identify problems; she points toward solutions. Her work is grounded in Critical Disability Theory (CDT) and the Neurodiversity Paradigm.

- Critical Disability Theory argues that many of the struggles autistic people face aren’t because of autism itself but because of ableist structures—schools, workplaces, and cultural attitudes that aren’t built to include them.

- The Neurodiversity Paradigm reframes autism as a natural variation of human diversity, not a defect.

Seen through this lens, the problem isn’t autistic individuals failing to adapt. It’s systems failing to value and support them.

Bliss makes four key recommendations for schools, educators, and policymakers:

- Tackle Stigma and Masking Directly

Schools need to create emotionally safe spaces where diverse expressions are welcomed. Teachers should work with students collaboratively, not in ways that demand compliance. - Redefine Success on Individual Terms

Instead of tying “success” only to money or independence, educators should help students explore identities, interests, and goals that reflect their strengths and values. - Teach Advocacy Early

Self-advocacy should be seen as a civic skill, not just an accommodation. Students should practice disclosure, boundary-setting, and negotiation in environments that validate asking for support. - Make Transition Planning Student-Centered

Moving from school to college or work shouldn’t be a checklist exercise. It should involve project-based learning and co-designed pathways that embed emotional growth, identity exploration, and collaboration.

Why This Matters

Bliss’s study says that autistic young adults are not passive recipients of care—they’re active, capable individuals with emotional depth, resilience, and insights that can enrich society.

The real challenge lies in whether schools, workplaces, and communities will shift from deficit-based models (focusing only on what autistic people can’t do) to empowerment-based models (building on what they can).

Her research highlights that emotional intelligence isn’t fixed. It grows, adapts, and can be taught—but only in environments that validate identity and promote belonging. If we get this right, autistic young adults won’t just survive transitions to adulthood—they’ll thrive on their own terms.

In the end

Autistic young adults don’t need to be “fixed.” They need systems that recognize their worth, amplify their voices, and nurture their emotional intelligence without forcing them to mask or conform.

Bliss’s dissertation makes it clear, unlocking autistic potential means rethinking how we define success, how we teach emotional skills, and how we build a world where diversity is seen not as a deficit but as a strength.

Because in the end, the question isn’t whether autistic young adults can succeed. The question is: will society let them?